What is your AI System Risk Level under the EU AI Act?

As the European Union unleashes its landmark Artificial Intelligence(AI) Act, AI developers and users find themselves scrambling to navigate a complex regulatory landscape that promises to reshape the industry. At the heart of this sweeping legislation lies a nuanced, risk-based approach that could make or break AI systems: the higher the risk, the tighter the regulatory noose. With four distinct risk categories—each carrying its own set of obligations—the AI Act presents a Rubik's Cube of compliance that even the most seasoned companies are struggling to solve. As the countdown to implementation ticks away, one question looms large for every AI stakeholder: where does your system fall on this risk spectrum, and are you prepared for the regulatory mandate that follows?

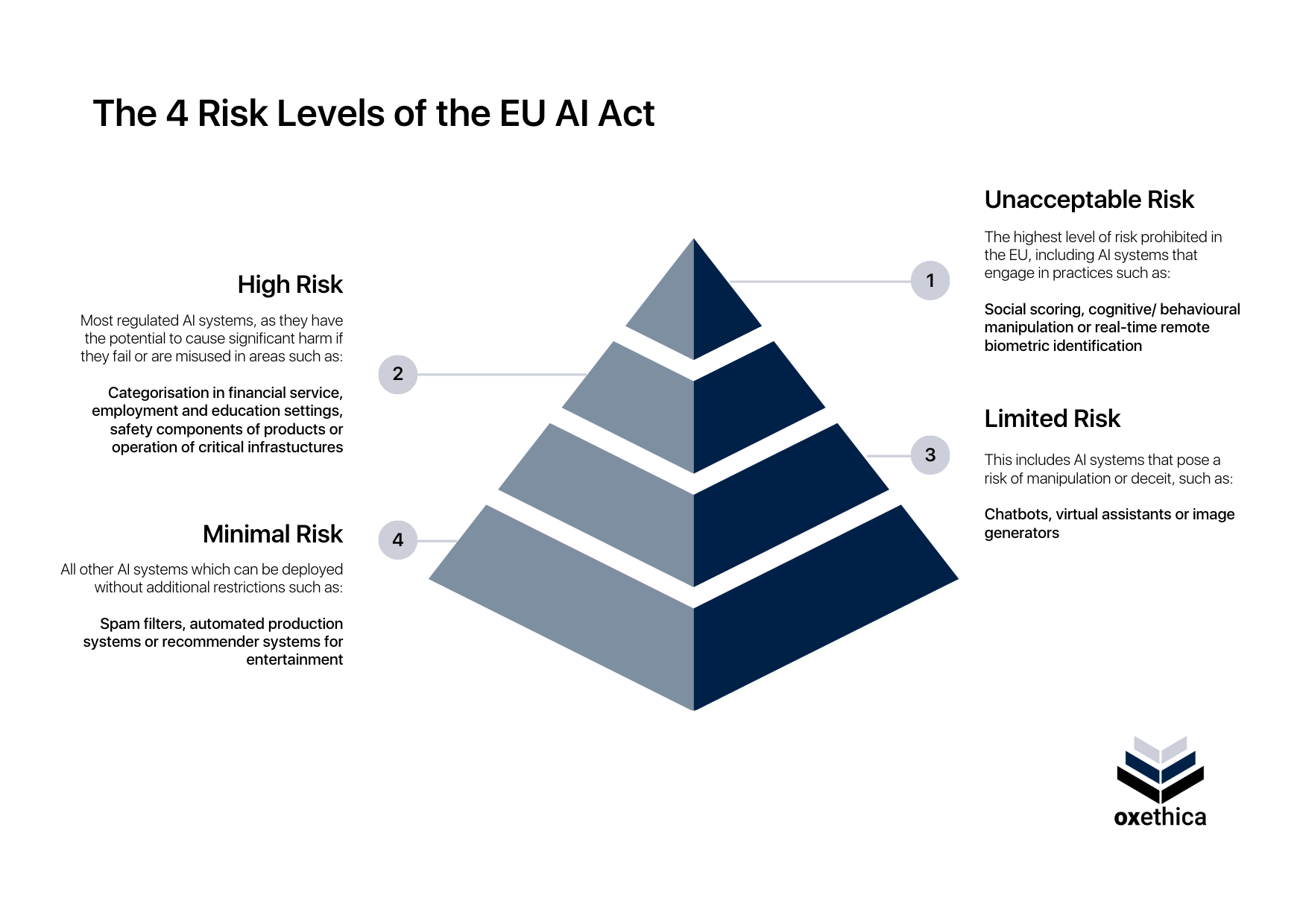

The Four Main Risk Levels

Unacceptable Risk / Prohibited Practices

The EU AI Act identifies “unacceptable risk” as its highest risk category, encompassing AI systems that pose serious threats to fundamental rights, democracy, equality, and freedom. These systems are strictly prohibited under the act. Specifically, the AI act bans AI systems designed to manipulate human behaviour and decision-making through subliminal techniques, as well as those exploiting an individual's vulnerabilities due to their social or economic status.

The Act also prohibits systems that process biometric data for remote real-time categorization, with far-reaching implications. This ban covers the creation of social scoring structures and the compilation of illegal facial databases. Real-time biometric identification is forbidden, except when used solely for verifying an individual's identity. The prohibition extends to profiling systems and technologies for emotional recognition, particularly when deployed in workplace or educational settings. These restrictions reflect the EU's determination to protect personal privacy and prevent potential misuse of sensitive biometric information.Providing or deploying any of the prohibited practices laid out in Article 5 of the AI act will be penalised with maximum fines.

However, it should be noted that the AI Act makes exceptions for a handful of very narrow use cases and scenarios. For example, applications in public security or law enforcement using real-time biometric identification may be subject to such exceptions.

High Risk

For the most part, the EU AI act addresses so-called high-risk systems, which are defined by two key conditions. Firstly, systems deployed as safety components of products covered by Annex 1 and requiring external audits are considered high-risk. Secondly, AI systems falling under any of the eight categories listed in Annex III, such as healthcare, education, or biometric data processing, are also classified as high-risk. Permitted AI systems processing biometric data face further stringent mandates, including third-party audits.

Several applications are particularly relevant for companies. First and foremost, categorisation algorithms in the financial service and insurance sectors are seen as posing a high risk due to potential algorithmic biases and discrimination. These systems face specific, additional compliance mandates to ensure the impact of fundamental rights has been assessed before launching the AI system.

In employment, high-risk systems include those used for recruitment, candidate selection, contractual decisions like promotions or dismissals, work allocation based on personal traits, and performance monitoring. In education and vocational training, systems affecting admission or access to educational programs, evaluating learning outcomes, assessing potential education levels, and proctoring fall under this category. Critical infrastructure management also involves high-risk AI, especially in areas like road traffic control and utilities such as water, gas, heating, or electricity supply.

Other high-risk applications, more prevalent in the public sector, encompass systems used in migration, asylum and border control, administration of justice and democratic processes, law enforcement, and access to essential public services.

Given their potential to pose considerable threats to fundamental rights, democracy, and safety, high-risk AI systems must undergo rigorous conformity assessment procedures. These assessments include audits of data governance, the implementation of a monitoring and quality management system, and registration in an EU database.

Limited Risk

The limited risk class addresses AI systems which may have a limited capacity to violate fundamental rights or pose a threat to safety, democracy, rule of law or the environment. This is because systems with limited risks typically process less sensitive or anonymised data, and are deployed in low-risk contexts such as algorithms for personalised advertisement recommendations, image generators, or chatbots.

Limited risk AI systems mainly have to comply with the transparency mandates of the AI Act to ensure accountability and explainability. This includes…

- clearly informing users that they are interacting with AI

- clearly marking AI generated content

- providing comprehensive explanations for intended use cases and data processing principles

- maintaining documentation ensuring compliance with ethical and safety standards.

Minimal Risk or No Risk

AI systems classed in the minimal risk category are not subject to regulation and legal obligations because they are not predicted to constitute a threat to fundamental rights, the rule of law, democratic processes, or the environment. For example, AI powered spam filters, systems for optimising product manufacturing, or recommender systems for entertainment services would fall under the minimal risk category. This is because they do not process sensitive data, perform narrow procedural tasks, and are not meant to replace or influence human assessment or oversight.

The EU encourages developers and deployers to adhere to a voluntary code of conduct and follow the proposed requirements for trustworthy AI despite a low-risk rating. It is crucial, however, that developers and deployers continuously assess the safety and compliance of their AI system should the data input or use case change. Moreover, with further progress of AI technologies it is likely that the EU will alter and expand regulations. Therefore, monitoring the risk classification of your AI system is imperative.

The Risk Class of General-Purpose AI Models

What is a General-Purpose AI Model?

General-purpose AI (GPAI) models have been a controversial subject in the EU during the AI act negotiations that held up its passing into law. But what exactly are these models, and why have they sparked such debate?

GPAI models have rapidly risen to prominence, transforming the AI landscape. Typically built on deep learning algorithms, these systems can perform a wide array of tasks. They process vast amounts of diverse data, including text, images, and audio, earning them the moniker "foundational models." This term reflects their capacity to serve as a base for more specialised AI applications within larger systems. Other labels include “frontier AI”, to denote their advanced levels of development. Well-known examples include Large Language Models like OpenAI's ChatGPT, Google's Gemini, and Anthropic's Claude, as well as multi-modal systems like Dall-E, Image, Sora and the like.

The versatility of GPAI models is both their strength and a source of regulatory concern. Their ability to produce numerous intended and unintended outcomes makes them inherently complex to understand and control. Recognizing this challenge, EU legislators have dedicated specific sections of the AI Act to GPAI regulation, dealing with potential “systemic risk” that these systems may pose to society.

Systemic Risk

The complexity and opacity of GPAI are considered a serious risk source by experts and legislators. The AI Act introduces the concept of “systemic risk” for GPAI models that exhibit so-called “high impact capabilities”. These capabilities are - for better or worse - defined by computational strength and the proportionate risk to cause negative outcomes for society or the environment.

High impact capabilities are determined by factors such as volume of training data, number of parameters, or the level of autonomy and scalability. The act currently defines GPAI as having high impact capabilities when the “(...) cumulative amount of computation used for its training measured in floating point operations is greater than 10(^25)” (Article 51, Paragraph 2).

Providers of GPAI models face a multi-tiered set of obligations under the AI Act. Beyond complying with the requirements set by their model's risk level, they must adhere to additional considerations, particularly if their model poses systemic risks.

For GPAI models classified as having systemic risks, providers are obligated to conduct more rigorous testing protocols. This includes employing adversarial testing techniques to probe the model's vulnerabilities and potential failure modes. Such comprehensive testing aims to uncover unforeseen behaviours or outputs that could have far-reaching consequences.

Moreover, these providers bear a heightened responsibility for ongoing monitoring and incident reporting. They must promptly report any significant incidents or malfunctions arising from the use of their systems. This rapid reporting mechanism is crucial for swift mitigation of potential harms and for informing future regulatory adaptations.

Cybersecurity also takes centre stage in these additional obligations. Providers must ensure their GPAI models maintain appropriate levels of cybersecurity, safeguarding against potential breaches or manipulations that could exacerbate the model's systemic risks.

It should be noted that the indicators and benchmarks for systemic risk are likely going to be subject to change in accordance with progress and innovation of technologies. The exact details of responsibilities and obligations for general purpose AI models can also be found in Articles 51 through 56 and Annex XIII of the AI Act.

Transparency is Key

Overall, the AI Act mandates a transparency principle to all AI applications to build trust through explainability and accountability. The amount of detail required to maintain transparency depends on the risk level of an AI system. The EU has not yet declared exact rules for transparency and is going to alter and specify them as the AI Act comes into practice. Overall however, transparency is broadly defined by ensuring user awareness and maintaining explainability. So far, all providers are obligated to demonstrate exactly what data their system processes and how it arrives at its outputs regardless of its risk class. They need to ensure that downstream users can fully access information on the kinds of data the AI has been trained on and the intended use of the model or system.

How do I Assess the Risk Level of my AI System?

Determining the risk level of your AI system is a crucial step in ensuring compliance with the EU AI Act, but it can be a complex process. oxethica offers comprehensive support for your AI governance and compliance needs, simplifying this critical task.

Our specialised platforms and solutions enable you to create a detailed AI inventory, cataloguing all the systems you have in place. More importantly, we provide tools to accurately identify the risk level of each AI system, a key requirement under the new regulations.

Beyond risk assessment, Oxethica's solutions offer a tailored list of requirements necessary to make your AI compliant with the Act. Our platform facilitates the efficient collection and secure storage of compliance-related information, streamlining your journey towards AI governance.

By partnering with Oxethica, you can navigate the intricacies of AI risk assessment and compliance with confidence, ensuring your AI systems align with regulatory standards while optimising their performance and reliability.

More on AI regulation

The European Union’s General-Purpose AI Code of Practice: The Key Points at a Glance